Toronto's Development Charges Rise Visualized

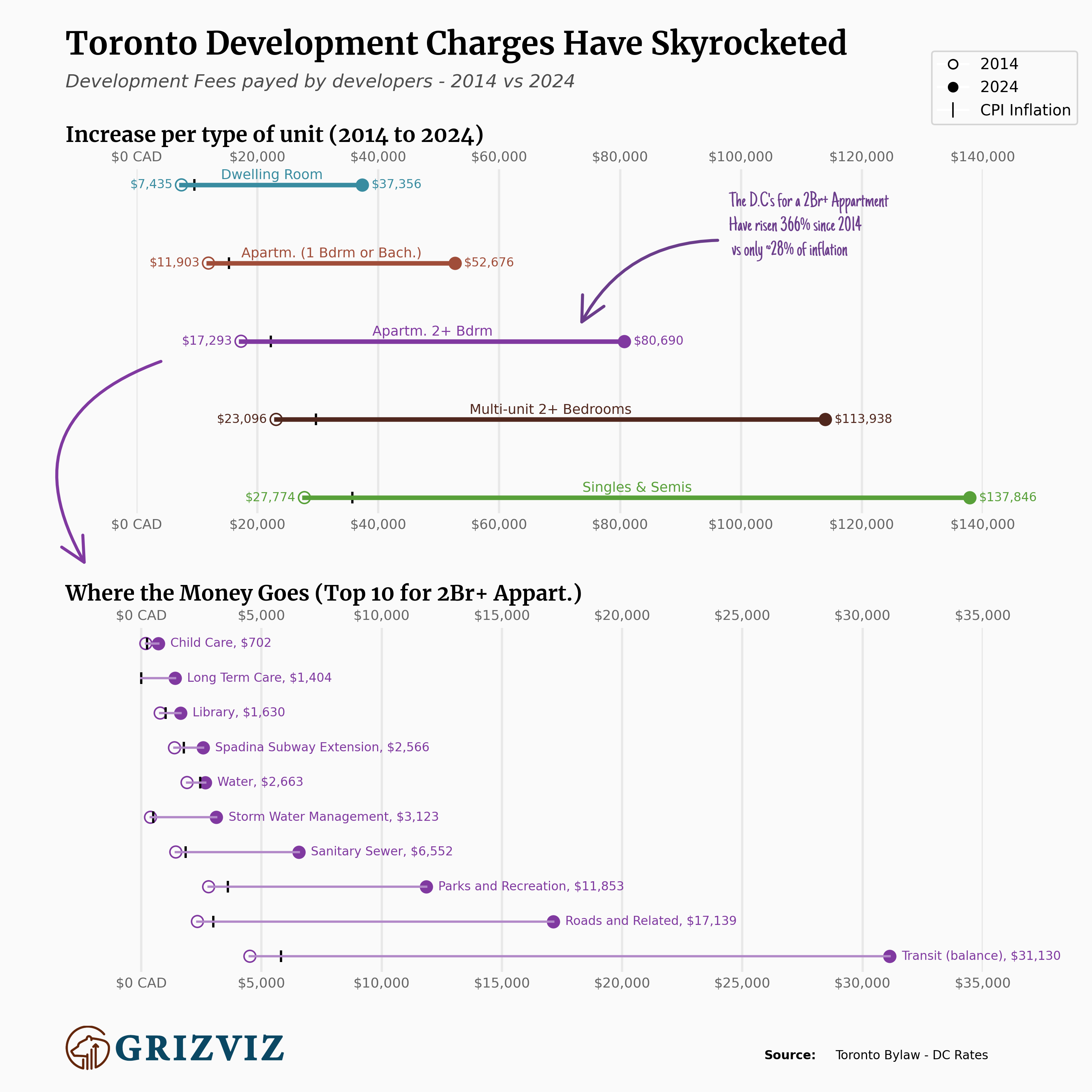

Development charges on a single family home in Toronto are currently over $135,000 in 2024 - an amount that inevitably raises housing prices. What are they and how do they relate to the housing crisis?

The housing crisis has been a subject at the top of Canadian minds for over a decade now, with an even larger focus the last few years. Many causes have been named - zoning laws, perceptions of developer greed, too much demand due to short term immigration skyrocketing recently, investors buying up available stock - just to name a few. In short, they all come down to too much demand for the supply we have. Many solutions have been proposed or adopted as well, mostly on the demand side - an FHSA, longer mortgages, various first time homebuyers advantages, etc.

However, not as much has been adopted on the supply side. There are many more variables in play. Just to name a few - a house is not built instantly, sites have to be assessed and selected, permits have to be drafted and approved, the materials have to be purchased, the houses actually need to be built and finally, they have to be sold - at a profit.

One of the topics we’ll explore in depth on GrizViz is the minimum cost of a housing unit - before factoring in the risks and opportunity costs for the developer to expect to make a profit and decide to build a house. That’s where development charges come in.

Development charges are fees paid by developers of new buildings during the permit stage. The idea behind them is that any new unit requires new infrastructure. Water has to be connected in and then the wastewater has to be collected and brought to treatment centers. A new block requires new roads, new transit, new utilities, new emergency services. These charges are meant to pay for the growth in infrastructure. Specifically, they are defined in municipal Bylaws. For Toronto, the current bylaw is BY-LAW 1137-2022 which passed in 2022. This bylaw specifies what services the City of Toronto uses the fees for. The top five services - and the amount per 2+ Bedroom Apartment, as outlined in the plot, are:

- Transit (balance) - $31,130

- Roads and Related - $17,139

- Parks and Recreation - $11,853

- Sanitary Sewer - $6,552

- Storm Water Management - $3,123

The services that can be paid for through development charges are quite detailed. They are meant to cover the capital costs of new infrastructure - and not the operational costs to keep it running or maintain it. In the case of parks for example, it mentions “Parks and recreation services, but not the acquisition of land for parks”. To see all allowed services, you can read the most recent version of the Bill here

It is important to understand that despite these charges being paid by the developers, the cost inevitably trickles down to the buyer. No developer would embark on an unprofitable project - the sale price must thus increase to keep the developer in the green. This is even more true in a hot market - which has been the case on Ontario. In a slow or declining market, a portion of the fees can be eaten by the developers. It also has an impact on resale home values. In a hot market, the resale homes would be in higher demand in the short term, leading to a catch-up in prices.

When did development charges start?

In 1987, the Ontario Government passed the “Development Charges Act” which detailed the process by which municipalities can pass their own development charges by-laws. This Act got heavily revised in 1997 into the Act we still have today (with some minor amendments including recently in 2024 ). It details what studies must be done prior to charging development costs, and what services those fees can be applied towards. These studies must also be renewed every five years.

Toronto then passed a Bylaw defining development charges it levies on developers, regularly updating the rates following the completions of studies every five years. The plot above shows the drastic change over the last decade.

Tradeoffs of development charges

As mentioned, the idea with development charges is that ‘growth should pay for growth’. When new houses and apartments are built in a city, it requires many new services such as water and wastewater services, emergency services, new parks and recreation facilities, and many more. The fundamentals of Development Charges are straightforward - the people that want to build more should foot the bill for the cost. However, it’s not that simple.

A week and a half ago, the editorial board at the Globe and Mail published an opinion piece on this subject called ‘The true cost of soaring development charges on new homes’ It argued that although the fundamentals are defensible (that buyers of new homes should pay for their own infrastructure), the reality is that municipalities, existing homeowners and even provinces have gotten too used to the freedom of these charges. They are too convenient. They prevent raises in property taxes and prevent widespread opposition to new projects.

A first example listed was in Kitchener where $126.2M out of a $144M new sports facility are to be paid through development charges and will have no impact on property taxes. Another is the fact that in Toronto, a buyer/builder of a semi-detached new home will pay nearly $4,000 CAD for the Spadina Subway Extension that opened 7 years ago. These charges are a convenient way to protect the existing homeowners from paying for projects that they too will reap the benefits of. One could easily argue that someone living in an established older neighbourhood elsewhere near Line 1 will use the Spadina Extension much more often than a new homeowner in Etobicoke or in Scarborough despite the latter still paying for it’s construction.

Professor Emeritus Dr. Andrew Sancton from Western University goes much deeper in his report ‘Reassessing the Case for Development Charges in Canadian Municipalities’. He presents the case that development charges lead to many undesired incentives and outcomes - including higher housing prices for everyone. It is worth reading the report as it covers too much to accurately summarize here. However a few key points include:

- Growth and non-growth related spending are often not fully localized.

- It is very common to pay for infrastructure you do not personally make use of. However, with averaging costs over all development charges (whether in greenfield or re-development regions, downtown or on the outskirts), you end up with the following analogy: “If we go to an all-you-can-eat buffet restaurant, we expect everyone to pay the same amount regardless of our appetite. But, if we order à la carte, we don’t expect to split the bill equally with a neighbouring table.”

- Most capital spending is lumpy to some extent. It would not make sense to build a sewer system only for the new development. You would want to build infrastructure that could support future growth as well. However, all that would be on the burden of the current generation paying for it today.

Some argue that not all this should be put on the shoulders of the new development - and by extension new home buyers. A comparatively small increase in the property taxes for the entire city can help cover some of the shared infrastructure of the new developments - transit, libraries and parks for instance.

Development charges are also not the only fee charged when a new home is built. According to a report from the Building Industry and Land Development Association (BILD), other significant charges include the parkland dedication fees and community benefit charges (CBC). They assert that for a low-rise development the total fees amount to nearly 200k ($195,832) in Toronto.

With Ontario’s housing starts down 16.9% year over year, per the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, it is important to consider the effect very high development charges have as a barrier for new - and often first time - homebuyers in Ontario.

Further Readings

This chart and text can only cover a brief overview of the much more complex topic of development charges, other fees and taxes and the overall housing market. For instance, this chart only covered residential development charges. A slightly different system is used for non-residential charges. To learn more and follow the latest developments, you can reading the following:

- Dr. Mike P. Moffat - A Canadian economist and professor of Business, Economics, and Public Policy. He has written for numerous publications, including The Globe and Mail and online on Substack & Medium. He’s active on X and Bluesky where he often discusses housing, various Canadian policies and development charges.

- Open Council published a detailed document to add much more information relating to these charges - comparison to other cities, changes in legislation over time, what other fees exist during construction, a comparison to the ‘Montreal Mode’ which does not have development charges, and much more. You can read it here.

- A useful study prepared for BILD (Building Industry and Land Development Association) to see the data compiled for Developers - see the industry’s state as they see it.